American Ruins W? A nationwide abandoned-edifice tour offers monumentally haunting clues.

This country’s unmatched and unlimited industrial might helped define the 20th century. But that was then, and this is now.

Crystal Mill: Marble, Colorado

When you first see the Crystal Mill—a former powerhouse cantilevered over a rushing river at an altitude of more than 10,000 feet—the first word that you may think of is Jenga. After all, with rough-hewn beams crisscrossing their way up to the mill’s main rooms, the whole structure seemingly has a wobbly future. But despite appearances, the mill—which dates to the 1890s—has proved remarkably sturdy even though it has been out of service for more than a century.

Part of that durability comes from the outcropping of rocks on which the mill is built, stone that also forms the bed of the Crystal River, giving the setting an even more striking appearance, as water constantly cascades past. That steady flow was key to the mill’s existence, spinning a waterwheel that powered an air compressor for the Sheep Mountain Tunnel, a slip of silver that lured a generation of workers to this rugged and remote chunk of the Centennial State.

Many of those who came to delve into the mountains lived in the nearby town of Crystal City, which, like its namesake mill, still stands, albeit largely abandoned. The town was once home to 600 or so souls, working at various mines and drinking to keep warm, though a crash in the price of silver emptied out the barrooms (and most of Crystal, too).

Those who make the trip from places like Aspen—about 20 miles northeast, but a nearly two-hour drive snaking through the mountains—are treated to a picturesque look into Colorado’s history, which was long tied to what lay beneath its soil. Framed by snowcapped peaks of the Elk Mountains and lush treescapes, the mill is commonly cited as one of the most photographed locations in Colorado.

The Sheep Mountain mine closed in 1917, taking the mill’s meaning-of-life along with it. In late 2021, plans for a “high-end winter and summer retreat,” offering backcountry skiing and fly-fishing, were reported in local newspapers, hot on the heels of a music festival that sprouted along Crystal City’s long-overgrown main street. But more than music, the main draw here remains the mill itself, still standing tall, despite its seemingly precarious perch.

Port Richmond Generating Station: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A hulking neoclassical behemoth on the banks of the Delaware River, the Port Richmond Generating Station bears both the scars of its age and the faint etching of its past owner and purpose: the Philadelphia Electric Company.

The building’s birth dates to the Jazz Age, when Philadelphia was booming and needed energy to bring light to its eventually Springsteen-serenaded streets. The method of making electricity was simple and sultry: Coal-fired boilers would superheat water, the resulting steam would spin turbines and converters would channel the spark out into Philly’s territory.

Despite its industrial ethos, the company wanted the station to look good, too, so it hired John T. Windrim, the famed Philly architect who had designed a series of anciently inspired buildings around town. For the Port Richmond station, Windrim’s vision included an arching, skylighted turbine hall that was “modeled after the ancient Roman baths,” according to Jack Steelman’s Workshop of the World, a study of the city’s industrial history.

That building opened in 1925, though only part of Windrim’s plan came to fruition: The Depression, after all, dramatically reduced the need for power, and the prospects for generating a profit off it. Still, improvements and addendums kept it purring till the mid-’80s, when it finally closed after six decades in service.

Since then, neglect and the Northeastern winters have pockmarked the glass ceiling of the wide-open main hall, leaving it with dozens of broken windows, casting slivers of sunshine on the floor below, which sometimes floods, as rain and snow pelt the stone carapace and puddles therein. A tree sprouts from the rooftop and rust cakes smokestacks.

Massive tubes and bulbous boilers still create a sense of outsized, Alice in Wonderland wonder. Crust-covered railings and balconies surround the eerie central atrium, and in a mothballed control room, every knob, monitor and indecipherable gauge is coated with dust, even as discarded papers still litter the floor. The facility’s coal tower remains standing in the middle of the Delaware, connected to the riverside ruin by an arm of metal, but vandals and scrappers have had their way with some of the fixtures inside and outside the plant. Rain and snow fall inside the structure during storms, and tidal waters sometimes lap at the ancient machinery.

Even so, the Richmond plant has managed to foster some fame for itself in its retirement, appearing as a post-plague psych ward in the 1995 movie Twelve Monkeys and, more recently, as a backdrop for menacing machines in 2009’s Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (as was its sister plant, the Delaware Generating Station, a little farther downriver).

The parcel of land on which it sits was sold to a local development company in 2019, and the building’s future is unclear. Until then, the Richmond continues to watch the city around it evolve, with new skyscrapers rising around it like the steam that once billowed inside.

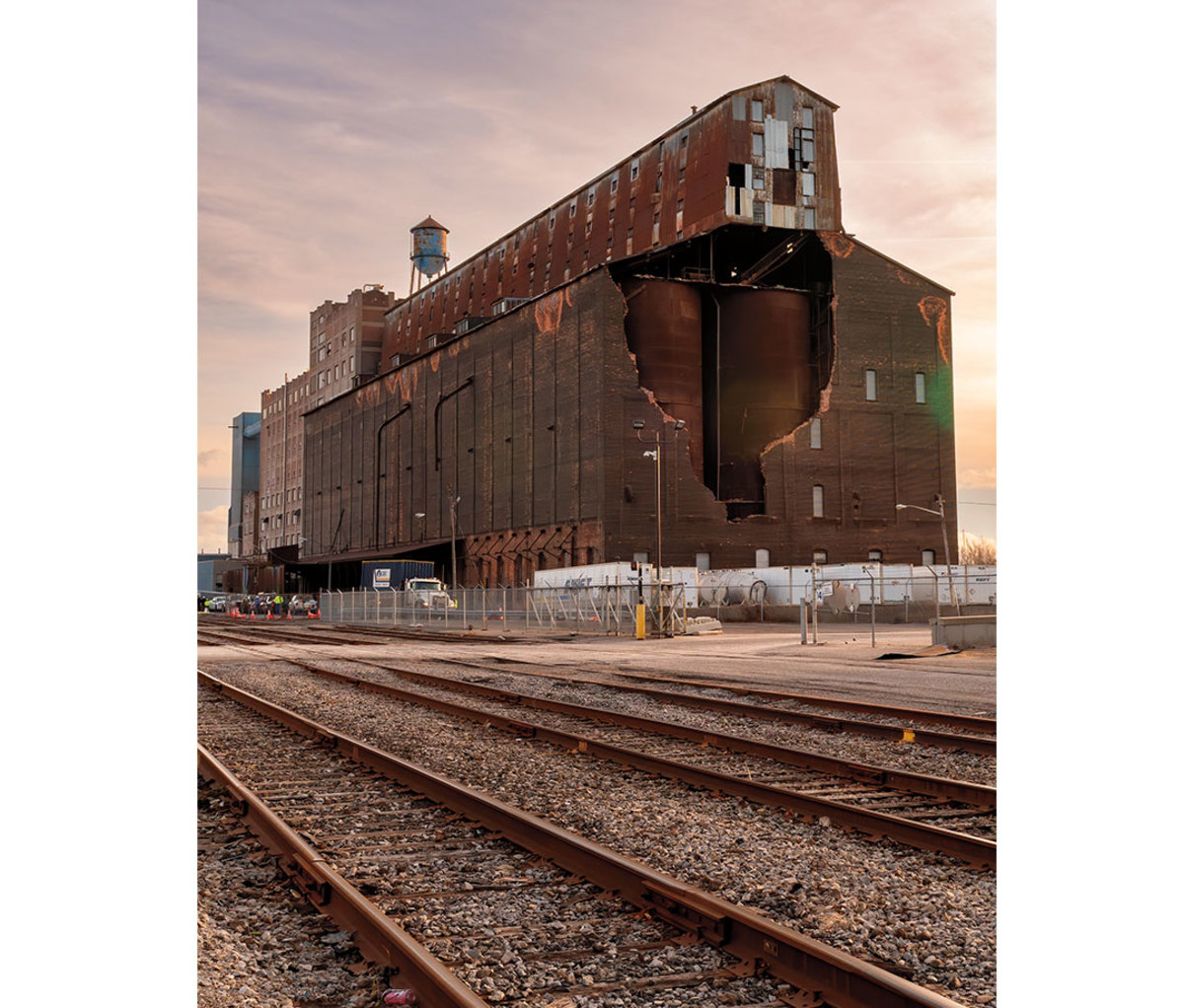

Great Northern Grain Elevator: Buffalo, New York

Long before Buffalo was known as the home of chicken wings, beef-on-weck or even the Bills, the Queen City was considered the grain-storage capital of the United States. That distinction—a weird one, to be sure—came in large part because of a series of soaring cement grain elevators that were built on the edge of Lake Erie, where Midwestern-grown wheat would come east on ships, before being sent to market along the Erie Canal or other byways.

Perhaps the most notable of these structures—at least for grain-elevator aficionados—was the Great Northern, a 15-story, brick-cladded “cathedral,” according to Gregory Delaney, a clinical assistant professor at the University at Buffalo’s architecture school.

Once fueled by electricity generated by Niagara Falls, about 20 miles northwest, the Great Northern was essentially a giant machine disguised as a building, using a series of pulleys, hoppers and conveyers to move grain from trains and ships to a series of steel bins inside. The building’s brick cladding kept the steel bins safe from the harsh winters and raking lake-side winds.

Buffalo’s connection to the wheat trade was once so intertwined that Buffalonians joked that the whole city “smelled like Cheerios.” Eventually, however, as trucks and planes began to make canal-travel obsolete, many of the city’s grain elevators fell into disuse, including the Great Northern, which closed in 1981.

The building’s current owner, a subsidiary of the food giant Archer Daniels Midland, acquired the building in 1992, and has sought several times to demolish it, leading to fierce battles with local preservationists, including an ongoing court saga. The pressure to tear down the Great Northern intensified in late 2021, when a powerful winter storm ripped away a section of the building’s brick on its northern wall, leading ADM to seek an emergency order to tear it down.

Conservationists insist the elevator is still structurally sound even as developers have floated various ideas for renovating it—a museum, apartments, a cultural center. Architectural experts like Gregory Delaney say that its destruction would be a major historical loss. Other fans agree.

“It’s hard for outsiders to believe, but people in Buffalo really cherish and value the elevators,” said Tim Tielman, the executive director for the Campaign for Greater Buffalo History, Architecture & Culture, which has sued to stop the demo. “They are big, gritty survivors, and this is the grittiest of them all.”

Tintic Standard Reduction Mill: Outside Gosben, Utah

Nestled into an arid hillside about an hour south of Salt Lake City, the Tintic Mill lived fast and died young, processing silver ore with the so-called Augustin method for a brief shining moment in the early 1920s, before being supplanted by more sophisticated means.

While its roots are a century old, the Tintic—so named for the mountain range in which it sits—sometimes resembles something even more ancient: its empty foundations suggesting a lost Aztec outpost, perhaps; its vacant bins evoking the ancestral, indigenous caves of New Mexico’s Bandolier National Monument. From other angles, the old mine looks vaguely futuristic, with its rounded tanks resembling the helm of some grounded starship, or maybe a lost and labyrinthine Cubist sculpture, magically transported from Paris to the middle of nowhere.

The Tintic’s location only intensifies its sense of otherworldliness. Located just outside Goshen, UT, the mine is surrounded by Martian desolation, though that remote—and occasionally rattlesnake-friendly—vibe has done little to discourage a steady stream of admirers.

Utah officials have not been amused by their interests, however, warning that the Augustin method involved a bevy of unpleasant and distinctly poisonous chemicals, including arsenic and lead, which still pollute the site—and those that traipse past “No Trespassing” signs to visit it. The site also has scientific and historical import; in 1978 it was included on the National Register of Historic Places, with archivists noting its engineering.

Indeed, as toxic as it was, the hillside design of the Tintic was also clever, using the gravity of the slope to facilitate the extraction of silver from its ore. Despite that ingenuity, the mine was a financial bust—costing millions in 2022 dollars for only a few years of use—and quickly made obsolete by cheaper methods of leeching out riches from rocks.

And while other nearby extraction- era mines also faltered and failed, leaving behind ghost towns and other odd tourist attractions, few seem to draw the artistic-minded souls who have decorated Tintic over the years. Enormous eyes and cryptic initials now stare out at the mountains beyond, as flowers and faces stare at visitors from the curved walls of the long-drained water bins.

As part of the Goshen Warm Springs Wildlife Management Area, the land is managed by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, which has kept it closed it to the public. But considering the off-the-beaten-track appeal of locations like Marfa, TX, one could imagine a quirky museum in such a locale, if only they could get rid of the mine’s poisonous past.

And, of course, the rattlers.

Satsop Nuclear Plant: Elma, Washington

Once part of the largest nuclear power plant construction project in the nation’s history, the Satsop never saw a single flicker of fission. The multibillion-dollar plan ground to a halt in 1983 because of a financial meltdown by its owner—the Washington Public Power Supply System, sometimes nicknamed “Whoops”—resulting in the largest municipal bond default in U.S. history at the time.

Despite its bankrupt past, however, Satsop still looks the part, with a pair of completed cooling towers; demolishing them would have cost even more money that the developer didn’t have, so they remained standing, even as the national appetite for nuclear power faded, a trend no doubt edified by the terror of the 1986 Chernobyl accident.

Satsop continues to try to turn a buck, having been incorporated into a local business park made up of various formerly nuclear-minded industrial spaces. (At least one warehouse was tapped to grow marijuana, which is legal in Washington.) The site offers up a tech center and workforce training center, though it has also been used for slightly more exciting activities, such as military and first-responder training, complete with hazmat suits and armored equipment, which, of course, is never the most comforting thing to see around a nuclear plant.

“What’s so BIG about Satsop Business Park?” reads a come-on on the group’s website. “Everything!”

Indeed, the towers soar hundreds of feet in the air, poking their gray heads far above the mist-watered trees that surround them (and most of Elma, southwest of Seattle). Their unique shape—elegantly curved walls, tapering and turning up to the often-cloudy sky—make for curious acoustics, as do the thick concrete walls of some parts of the facility, with some companies doing sound research inside. A metal stairway climbs the side of each tower, leading to a narrow walkway nearly 500 feet in the air; there is also the still extant reactor building, and a series of tunnels, some hundreds of feet long, that bore underneath the Satsop.

Before Covid shut down, well, “Everything!,” such unique features made the facility popular with sci-fi filmmakers—the Transformers series used the location twice—as well as some more experimental souls. That includes Japanese-born, Seattle-based artist Etsuko Ichikawa, who created an eerie short film there after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in her home country drenched and partially destroyed another nuke: the Fukushima power plant, leading to a massive release of radioactivity.

No such worries envelop Satsop, however, whose pre-Enron-era cash crunch never let it go nuclear. And for the time being, not much art is happening there, either, as its owners have stopped rentals for shoots, leaving both killer robots and trippy-film makers scouting for other backdrops.

Six Flags New Orleans: New Orleans, Louisiana

Although not a 20th-century industrial colossus shuttered by the gig economy, the fading fun that is represented by the Six Flags New Orleans—swamped by the 2005 storm Katrina, which killed nearly 2,000 people and caused more than $100 billion in damage—is trenchant, with abandoned rides still beckoning a crowd that never arrives.

Built under the name Jazzland, and opened in 2000, the $130 million wonderland was originally meant to represent the always vibrant vibe of NOLA, with areas named Cajun Country, the Goodtime Gardens and, naturally, Mardi Gras. Leaning on the city’s culture and heritage, the park offered live music and glittering beads to visitors, just like Bourbon Street; “When the Saints Go Marching In” was known to serenade those waiting in line for the next thrill.

And unlike many of New Orleans adult-oriented attractions, Jazzland, which was taken over by Six Flags in 2002, was meant for family fun, with a giant wooden roller coaster with a rockin’ name, the Mega Zeph; the Muskrat Scrambler, which specialized in brain-rattling hairpin turns; and eventually the loop-crazy, neon green Jester, recalling Batman’s nemesis, the Joker. As that suggests, Six Flags had added a DC Comics tie-in, with an inverted coaster devoted to the Caped Crusader.

Indeed, a superhero might have been called for in August 2005, when Katrina roared ashore, making landfall near New Orleans with winds well in excess of 100 mph, drenching rains and a catastrophic storm surge. The damage at Six Flags was extreme: Up to seven feet of water cascaded into the park, spilling through turnstiles and into the machinery of rides, destroying their electronics and other parts, and forever stilling them.

Closed for Storm, a 2020 documentary about the park, outlined much of the damage, as well as the ongoing upset among New Orleans residents who feel that the park’s abandonment is symbolic of the neglect still plaguing parts of the city.

In 2009, Six Flags negotiated out of its lease with the city, which took back the land. Over the years vandals and graffiti artists made their way into the remains, even as curiosity-seekers sought it out, too, roaming through buildings where 2005 calendars and promotion plans for that fall still hang on the walls.

https://ift.tt/rVNby9a September 01, 2022 at 04:35AM Men's Journal

Comments

Post a Comment